For reference regarding what flaws in I've done so far in scattered episodes over the last three weeks, this is the work in progress. Be warned: it is messy, and skeletonish in places. As ever with me, mine out of it what you can if you're interested, but don't expect too much value.

Monday, January 17, 2011

Methodological flaw?

Some explanations are in order. One of the things I have been doing over the last several weeks is listening to the "Induction in Physics and Philosophy" and the "Objectivism Through Induction" recorded lectures. I bought them at OCON08 but totally forgot about them until recently, and I still haven't finished OTI (I'm currently on lecture 5). They are proving to be extremely valuable... and also making me question the extent to which I have gone wrong in what I thought was proper inductive validation by oneself of another's findings.

Of present concern is how I had tackled economics, which I began questioning when I wondered if I had been wrong to some degree in the method. What I had been doing, at least to some extent, was effectively Aristotle's induction-as-suggestion method.

For this I had gathered a host of examples, both those themselves mentioned elsewhere (Merton's original paper and Wikipedia, mostly), examples I recall from others' specific instances, and those of my own observation and experience, and then treated them as the data for a preliminary induction. The next step I took was to examine the causes (and I have come to the conclusion that there are but two direct causes and that the other causes of the phenomena are in fact causes of those first two causes), and so tie the phenomenon to various facts (the complexity of existence, human capacities for focus and evasion/pretence, other facets of volitional consciousness, and so on). Finally, I then sought to reduce all the critical concepts back to direct perception. It is the second step there - the tieing in with other facts - that I am finding is problematic in what I have done.

I am glad I caught this at an early stage rather than waste a large amount of time only to find out the fact of such wastage at a later date. I'd hate to be in a similar position to a researcher that von Mises wrote about, who spent - and thus wasted - almost his entire academic life in systematically calculating the elasticities of every significant commodity that people regularly consumed. Yet, for what I have done so far, I am not sure that I have done exactly what Dr Peikoff said was wrong. I was not avowedly looking for broader principles to deduce the law from... but until I spend time going over my work from scratch a second time and working to fully comprehend the lessons of OTI it may well be that I had been unwittingly making that mistake anyway, so don't expect further publication from me in the immediate future.

By the way, over the last week of December I realised that I - and evidently a great number of others - had been making a subtle mistake. There is a definite distinction between that which was unintended and that which was unanticipated, and the law applies to the latter, not the former. This was both Merton's original description, and also cross-ties better with all the implications that are in fact inferred from the law by most and all those that should be so inferred. But more on that when I do finish writing.

JJM

Of present concern is how I had tackled economics, which I began questioning when I wondered if I had been wrong to some degree in the method. What I had been doing, at least to some extent, was effectively Aristotle's induction-as-suggestion method.

For this I had gathered a host of examples, both those themselves mentioned elsewhere (Merton's original paper and Wikipedia, mostly), examples I recall from others' specific instances, and those of my own observation and experience, and then treated them as the data for a preliminary induction. The next step I took was to examine the causes (and I have come to the conclusion that there are but two direct causes and that the other causes of the phenomena are in fact causes of those first two causes), and so tie the phenomenon to various facts (the complexity of existence, human capacities for focus and evasion/pretence, other facets of volitional consciousness, and so on). Finally, I then sought to reduce all the critical concepts back to direct perception. It is the second step there - the tieing in with other facts - that I am finding is problematic in what I have done.

I am glad I caught this at an early stage rather than waste a large amount of time only to find out the fact of such wastage at a later date. I'd hate to be in a similar position to a researcher that von Mises wrote about, who spent - and thus wasted - almost his entire academic life in systematically calculating the elasticities of every significant commodity that people regularly consumed. Yet, for what I have done so far, I am not sure that I have done exactly what Dr Peikoff said was wrong. I was not avowedly looking for broader principles to deduce the law from... but until I spend time going over my work from scratch a second time and working to fully comprehend the lessons of OTI it may well be that I had been unwittingly making that mistake anyway, so don't expect further publication from me in the immediate future.

By the way, over the last week of December I realised that I - and evidently a great number of others - had been making a subtle mistake. There is a definite distinction between that which was unintended and that which was unanticipated, and the law applies to the latter, not the former. This was both Merton's original description, and also cross-ties better with all the implications that are in fact inferred from the law by most and all those that should be so inferred. But more on that when I do finish writing.

JJM

Labels:

Economics,

Philosophy,

Science

Sunday, January 16, 2011

CR and DR

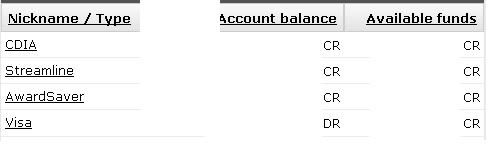

RealistTheorist quickly got the easy answer: CR is short for credit, DR is short for debit. One cookie.

The significance in this context comes from how that in the accounts presented the CR and DR are quoted from the perspective of my bank (Commonwealth Bank of Australia). Whenever one looks at one's bank statement what one is actually looking at is an extract from that bank's own accounting books, made available to the extent that one has the right to look at those books.

To the bank, the amounts listed as CR are liabilities. From their perspective these amounts are payable to me - CBA owes me those amounts (and hence they are also receivables in my own perspective). Here is the rub: in regards to my relationship with the CBA I have property in receivables from it, not in cash held by it. The amounts receivable by me and payable by CBA are the principals in a creditor-debtor relationship between us (likewise the sole DR is the amount I owe to the CBA on my credit card, and which amount to them is a receivables asset and not indicative of ownership in part of my physical cash holdings). This what the law, actual financial practice, and actual accounting practice have all now long been saying.

I don't know of any who made the following mistake, and I never made it, but it wouldn't hurt to give this warning against it: take care not to make the rationalist deduction "the amounts are listed as credit-side entries in accounting therefore they are items of credit in financial law". In fact it is the other way around, because the law takes priority and is what causes that financial-credit to be required to be listed on the credit-side in the books. Note that there are other reasons for listing credit-side entries in the books besides law-of-credit payables. Not every liability is an amount of financial credit, the equity holdings are also credit-side, and there even "contra assets" that are effectively credit-side even though their source is attachment to particular entries in the asset column (which is on the debit-side). The two contexts - accounting and finance - happen to use the same word, but what each context takes the word to mean is different to what the other takes it to mean and there is one point of overlap in referents.

The upshot of all this is that it further concretises the fact that in the real world today the bulk of the money supply is credit - in Australia as of Nov 2010, currency was $47b and demand deposits were $215b, giving an M1 of $262b. The credit in question is part of the money supply, additional to actual notes and coins, because I can easily reassign to others my property in claims upon the Commonwealth Bank of Australia. These monetised-credit mechanics are already here, fully in place and eminently capable of serving the needs of a sophisticated economy - and while something physical somewhere is necessary the use of credit as money does not strictly require physical cash (pay particular attention to paragraph 3 of this). The only thing that the financial sector need do if the courts begin taking heed of the epistemological complaints regarding the use of the word 'deposit' is simply to refrain from using that word. Until the rationalists on the topic of FRB understand that fact they are going to get absolutely nowhere in terms of theory and, in terms of practice in the event they actually succeed in influencing the courts, they will find themselves in the same position as the British Currency School when its members railed against FRB on notes in the mid 19th century: simultaneously listened to and promptly stepped around.

JJM

Update:

The numerical entry under the "available funds" column for my credit card line is the amount remaining unused from my credit limit. That's the amount I could further borrow but have not actually borrowed, so it isn't credit I've actually taken. Similarly, to get the CC relationship started I didn't have to make any initial deposits or whatnot in, so it isn't credit that I've granted the bank and the bank does not owe me anything either. In short, it is not as simple as saying "It's CR because it is available credit" in rationalist fashion as already warned against. So, here's another question for you - what does the implied credit-side classification of CR there signify? This time I don't know for definite, but I do have an educated guess that I am confident of.

The significance in this context comes from how that in the accounts presented the CR and DR are quoted from the perspective of my bank (Commonwealth Bank of Australia). Whenever one looks at one's bank statement what one is actually looking at is an extract from that bank's own accounting books, made available to the extent that one has the right to look at those books.

To the bank, the amounts listed as CR are liabilities. From their perspective these amounts are payable to me - CBA owes me those amounts (and hence they are also receivables in my own perspective). Here is the rub: in regards to my relationship with the CBA I have property in receivables from it, not in cash held by it. The amounts receivable by me and payable by CBA are the principals in a creditor-debtor relationship between us (likewise the sole DR is the amount I owe to the CBA on my credit card, and which amount to them is a receivables asset and not indicative of ownership in part of my physical cash holdings). This what the law, actual financial practice, and actual accounting practice have all now long been saying.

I don't know of any who made the following mistake, and I never made it, but it wouldn't hurt to give this warning against it: take care not to make the rationalist deduction "the amounts are listed as credit-side entries in accounting therefore they are items of credit in financial law". In fact it is the other way around, because the law takes priority and is what causes that financial-credit to be required to be listed on the credit-side in the books. Note that there are other reasons for listing credit-side entries in the books besides law-of-credit payables. Not every liability is an amount of financial credit, the equity holdings are also credit-side, and there even "contra assets" that are effectively credit-side even though their source is attachment to particular entries in the asset column (which is on the debit-side). The two contexts - accounting and finance - happen to use the same word, but what each context takes the word to mean is different to what the other takes it to mean and there is one point of overlap in referents.

The upshot of all this is that it further concretises the fact that in the real world today the bulk of the money supply is credit - in Australia as of Nov 2010, currency was $47b and demand deposits were $215b, giving an M1 of $262b. The credit in question is part of the money supply, additional to actual notes and coins, because I can easily reassign to others my property in claims upon the Commonwealth Bank of Australia. These monetised-credit mechanics are already here, fully in place and eminently capable of serving the needs of a sophisticated economy - and while something physical somewhere is necessary the use of credit as money does not strictly require physical cash (pay particular attention to paragraph 3 of this). The only thing that the financial sector need do if the courts begin taking heed of the epistemological complaints regarding the use of the word 'deposit' is simply to refrain from using that word. Until the rationalists on the topic of FRB understand that fact they are going to get absolutely nowhere in terms of theory and, in terms of practice in the event they actually succeed in influencing the courts, they will find themselves in the same position as the British Currency School when its members railed against FRB on notes in the mid 19th century: simultaneously listened to and promptly stepped around.

JJM

Update:

The numerical entry under the "available funds" column for my credit card line is the amount remaining unused from my credit limit. That's the amount I could further borrow but have not actually borrowed, so it isn't credit I've actually taken. Similarly, to get the CC relationship started I didn't have to make any initial deposits or whatnot in, so it isn't credit that I've granted the bank and the bank does not owe me anything either. In short, it is not as simple as saying "It's CR because it is available credit" in rationalist fashion as already warned against. So, here's another question for you - what does the implied credit-side classification of CR there signify? This time I don't know for definite, but I do have an educated guess that I am confident of.

Tuesday, January 4, 2011

Meanwhile on Netbank...

This is an extract from a screenshot of my internet banking website, half an hour ago:

Pop quiz: what do the "CR" and "DR" mean? What is their significance?

JJM

Pop quiz: what do the "CR" and "DR" mean? What is their significance?

JJM

Saturday, January 1, 2011

An unwieldy but valuable book

One of the books I got for myself a little while back is a paperback version of J A Schumpeter's 'History of Economic Analysis.' Contentwise it is straight-forward enough so far (I'm on page 93 after about 10 days of scattered reading episodes), though it does presume quite a large amount of knowledge and breadth of reading on the part of the reader. That is sobering, but at least this doesn't get in the way of comprehending the content.

The problem is physical - the pages are too small given that there are over 1200 of them! This makes it difficult to get comfortable while reading it, necessitating a firm grip that is both tiring after a while and creates the danger of damaging the pages or the cover. I'd hate to try reading this while on a plane or train (or automobile)! Its present physical format is best suited to books of tables and statistics that are delved into for minutes at a time (there are engineers' handbooks bigger than this), not for in-depth narrative. It should have been physically constructed with a smaller number of larger pages. The pages are a dash taller than A5, whereas ideally they should be one third taller and wider, giving a total of an extra 78% of text space per page and hence reducing the page count to somewhere around 750 to 800.

Another problem with this book is that the printing and binding got messed up. I estimate that there are about half a dozen or so leaves missing from the front of the book. Fortunately this is just Mark Perlman's introduction and the book itself (so far) is intact, so I wont bother with the trouble of sending it back halfway across the planet.

JJM

The problem is physical - the pages are too small given that there are over 1200 of them! This makes it difficult to get comfortable while reading it, necessitating a firm grip that is both tiring after a while and creates the danger of damaging the pages or the cover. I'd hate to try reading this while on a plane or train (or automobile)! Its present physical format is best suited to books of tables and statistics that are delved into for minutes at a time (there are engineers' handbooks bigger than this), not for in-depth narrative. It should have been physically constructed with a smaller number of larger pages. The pages are a dash taller than A5, whereas ideally they should be one third taller and wider, giving a total of an extra 78% of text space per page and hence reducing the page count to somewhere around 750 to 800.

Another problem with this book is that the printing and binding got messed up. I estimate that there are about half a dozen or so leaves missing from the front of the book. Fortunately this is just Mark Perlman's introduction and the book itself (so far) is intact, so I wont bother with the trouble of sending it back halfway across the planet.

JJM

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)